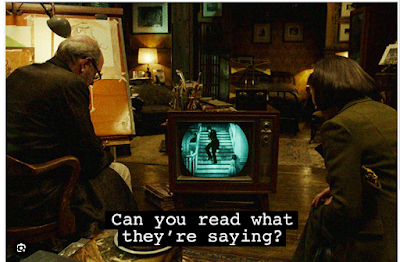

By 'subtitles' I mean the ones that appear at the bottom of a screen at the theatre or on your television. They are useful if the people on the screen are speaking a language you don't understand and the subtitles appear in a language you do, or if you cannot hear. The subtitles that appear after the title on a book constitute a different subject and it is a subject about which I have amassed a considerable amount of information. That will be presented to you if I ever stop being distracted by minor topics such as this one.

I am now old and so are my ears. My ability to hear has diminished along with many others and I have come to rely on subtitles or "closed captioning" when watching television (chyrons are somewhat different in that they offer words at the bottom of the screen directing you to something else you should be watching or worrying about.) Apparently many people, even the younger versions, are reading subtitles while watching what is on the screen. That readership is increasing among viewers is not disputed and if you search for articles about subtitles you will find many.

My purpose here is to direct you to an article which offers some explanations for why the subtitles are on, even if the characters speaking are not Irish. If you are older and don't know how to turn them on, call your service provider. In advance, you should turn up the volume on the phone so you can hear the reasons why you are being put on hold and, as well, listen to the music.

Here is the useful part and it represents only a portion of what the author has to say. You should read the entire piece which is by Devin Gordon and it came in a newsletter from the Atlantic magazine around June 6: "Why Is Everyone Watching TV With The Subtitles On?: It's Not Just You."

The good news, according to Onnalee Blank, the four-time Emmy Award–winning sound mixer on Game of Thrones, is that it’s not your fault that you can’t hear well enough to follow this stuff. It’s not your TV’s fault either, or your speakers—your sound system might be lousy, but that’s not why you can’t hear the dialogue. “It has everything to do with the streaming services and how they’re choosing to air these shows,” Blank told me.

Specifically, it has everything to do with LKFS, which stands for “Loudness, K-weighted, relative to full scale” and which, for the sake of simplicity, is a unit for measuring loudness. Traditionally it’s been anchored to the dialogue. For years, going back to the golden age of broadcast television and into the pay-cable era, audio engineers had to deliver sound levels within an industry-standard LKFS, or their work would get kicked back to them. That all changed when streaming companies seized control of the industry, a period of time that rather neatly matches Game of Thrones’ run on HBO. According to Blank, Game of Thrones sounded fantastic for years, and she’s got the Emmys to prove it. Then, in 2018, just prior to the show’s final season, AT&T bought HBO’s parent company and overlaid its own uniform loudness spec, which was flatter and simpler to scale across a large library of content. But it was also, crucially, un-anchored to the dialogue.

“So instead of this algorithm analyzing the loudness of the dialogue coming out of people’s mouths,” Blank explained to me, “it analyzes the whole show as loudness. So if you have a loud music cue, that’s gonna be your loud point. And then, when the dialogue comes, you can’t hear it.” Blank remembers noticing the difference from the moment AT&T took the reins at Time Warner; overnight, she said, HBO’s sound went from best-in-class to worst. During the last season of Game of Thrones, she said, “we had to beg [AT&T] to keep our old spec every single time we delivered an episode.” (Because AT&T spun off HBO’s parent company in 2022, a spokesperson for AT&T said they weren’t able to comment on the matter.)

Netflix still uses a dialogue-anchor spec, she said, which is why shows on Netflix sound (to her) noticeably crisper and clearer: “If you watch a Netflix show now and then immediately you turn on an HBO show, you’re gonna have to raise your volume.” Amazon Prime Video’s spec, meanwhile, “is pretty gnarly.” But what really galls her about Amazon is its new “dialogue boost” function, which viewers can select to “increase the volume of dialogue relative to background music and effects.” In other words, she said, it purports to fix a problem of Amazon’s own creation. Instead, she suggested, “why don’t you just air it the way we mixed it?”

The appearance of the subtitles on your screen also varies widely by platform—the streamers control that dial too—and some of them put more effort into the task than others. But their default typefaces are all clunky and robotic and bear no connection to the content. If they can beam Severance into our homes and invent dialogue-boost features, surely they can figure out how to let us pick our own typeface, or shrink the font size, or move the words to a different spot on the screen. You know who’d really benefit from that? Deaf people! Non-English speakers. Anyone who finds that subtitles make them feel included in the culture, rather than shut out of it. And maybe the ubiquity of words at the bottom of the screen will inspire filmmakers and showrunners to craft their own subtitles as a viewing option—you can watch this Jordan Peele art-house horror series with Hulu’s charmless sans serif or with Peele’s signature typeset."

Sources:

As mentioned, there are many. The graphic above is from: "Survey: Why America is Obsessed With Subtitles," Matt Zajechowski, preply.com, 03/06/2023.

I see that I hinted about my larger project on print subtitles in a post about: "Titling." Perhaps I should see if I can find my notes.