Prairie Schooner

Prairie Schooner is one of those periodicals you would have noticed in libraries that had dark shelving and lamps, and to which you would have been drawn by the good title. It has been around for over ninety years and, unlike most literary magazines, could be around a lot longer. It is published by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where the labour is supplied by those in the English Department. That, in and of itself, is no guarantee of longevity these days, but Prairie Schooner has a patron and the Glenna Luschei Fund for Excellence ensures that it is endowed in perpetuity.

Prairie Schooner is one of those periodicals you would have noticed in libraries that had dark shelving and lamps, and to which you would have been drawn by the good title. It has been around for over ninety years and, unlike most literary magazines, could be around a lot longer. It is published by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where the labour is supplied by those in the English Department. That, in and of itself, is no guarantee of longevity these days, but Prairie Schooner has a patron and the Glenna Luschei Fund for Excellence ensures that it is endowed in perpetuity.

It is a literary little magazine which means that it contains a lot of poetry and fiction, along with some interviews and reviews. You can subscribe to the quarterly for $28 (US) and you can have a peek at what it provides here. While most of the magazine is safely behind a firewall, one can look at the accompanying blog and read reviews and “Poetry News in Review.” As well, the journal supports an annual “Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction.”

Canadian readers can be assured that it does have some Canadian content and accepts contributions from Canadians. Back in 1993, “Prairie Schooner advertised widely throughout Canada in literary journals and writers’ newsletters, sent letters to dozens of women in an attempt to find the best, the most interesting, the most gifted and original and crafty (archaic: skillful, dexterous) women writers in Canada.” The result was an entire issue on “Canadian Women Writers,” which also includes an interview with Margaret Atwood (Vol.67, No.4, Winter, 1993). Thirty years before that issue there was one devoted to Malcolm Lowry which also includes an essay by Earle Birney (Vol. 37, No.4, Winter, 1963). More recently, Canadian sports fans should see the issue devoted to sports, (Winter, 2015) where you will find a poem about Jordin Tootoo. Foodies will also find a special issue devoted to that subject and an essay about herring and Grand Manan island (Winter, 2016).

If you are an ardent nationalist, unwilling to read anything published south of Point Pelee, you have a Canadian option - Prairie Fire: A Canadian Magazine of New Writing.

Post Script:

If you are curious about the type of person who funds such a literary endeavour you can learn more about Glenna Luschei (also known as Glenna Berry-Horton) by consulting Vol. 78, No.4, 2004 of Prairie Schooner. Apart from being generous, she also looks to be quite interesting. Among other hobbies, interests and vocations she is an avocado rancher.

If you are curious about the type of person who funds such a literary endeavour you can learn more about Glenna Luschei (also known as Glenna Berry-Horton) by consulting Vol. 78, No.4, 2004 of Prairie Schooner. Apart from being generous, she also looks to be quite interesting. Among other hobbies, interests and vocations she is an avocado rancher.

The university close by (Western) has a fairly good print run from 1927 to around 1980, but these volumes are all in a storage facility. Electronic access is provided to both the back and current issues via various electronic vendors such as JSTOR and Project Muse.

I will offer this slight bonus to the bibliophiles among my many readers. If you go looking more deeply for Prairie Schooner, you will learn that there are a couple of others produced by those who also thought the title attractive. They were newsletters published by people who found themselves in the Civilian Conservation Corps back in the 1930s. You can learn more here.

Back in 2014 the passenger pigeon was much in the news because the last one had died 100 years before. Martha was her name and she died in the Cincinnati Zoo (George was already gone). Like the parrot in the Monty Python sketch, she was dead, deceased, had ceased to be, was bereft of life and was no more. She was an ex-passenger pigeon. They are all extinct and there are no more.

Back in 2014 the passenger pigeon was much in the news because the last one had died 100 years before. Martha was her name and she died in the Cincinnati Zoo (George was already gone). Like the parrot in the Monty Python sketch, she was dead, deceased, had ceased to be, was bereft of life and was no more. She was an ex-passenger pigeon. They are all extinct and there are no more.

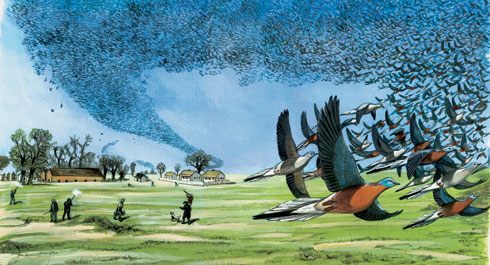

Even if you are not interested in birds you probably read some of those news accounts or you may have come across stories about how, many years ago, the flocks of passenger pigeons were sometimes so large they blocked out the sun and took days to pass. I just ran across one of those stories and it reminded me of the 2014 centenary of the extinction. This story takes place in Ontario and since I have not seen any references to it, I will present it here.

Pigeons on The Bruce

W. Sherwood Fox was a classics scholar and a president of the University of Western Ontario. He was also very interested in nature which is why he was mentioned in my recent post about John Muir, about whom he wrote an essay in The Bruce Beckons: The Story of Lake Huron’s Great Peninsula. He also wrote one about the passenger pigeon in the same book - “In the Day of the Wild Pigeon,” (Chapter 9). Here is how it begins:

“Of the many gifts that Nature bestowed upon The Bruce [ the Bruce Peninsula] one in particular will never be seen there again. Indeed, it has vanished from the face of the earth. It is known now only in museums, in slim dockets of old records, and in the memories of a very few men of exceedingly great age.( p.94)

The prevalence of the pigeon is noted by his father who arrived on The Bruce in the early 1870s:

“A picture of his entry into this frontier household was vividly stamped on his memory by two events of the first day: as he stepped from the steamer to the shore and walked to his summer quarters a vast flock of pigeons were flying from the east to their nesting area on the Peninsula and were casting a dark, swiftly moving cloud over the land. At his very first meal, supper, he was served adult wild pigeon. At breakfast the next morning this was the main dish, and for dinner too and then again for supper; indeed, it was the only piece de resistance - and a tough one at that.” (p.95)

The size of the roost was substantial even if one factors in a bit of local pride:

“The people of the region took pride in believing that the Peninsula was ideal country for the pigeons. It was common opinion around Colpoy’s [Bay] - an opinion based solely on rumour - that the nesting and roosting colonies were so numerous as to form virtually an unbroken chain running northward to a point not far short of Tobermory. Of course, that was not quite true, but to express doubts about it was counted in the new settlement as disloyalty to the wonderful greatness of the Peninsula. However, the only colony that Father himself saw was very long indeed: it began near Chief’s Point on Lake Huron just north of the Sauble River and extended in a broad sinuous line north to within a couple of miles of Lake Berford. That is, it ran from the west side of Amabel Township to a point two or three miles within Albemarle and slightly less than that distance north of Wiarton….” That the colony covered several square miles was all too obvious, but how many one could only guess without making a special expedition to determine the exact figure.” (pp.95-96)

Here is how the essay ends:

“But never again will anyone, in The Bruce or elsewhere in North America, know a surfeit of the passenger pigeon. It has gone forever. In The Bruce its numbers began to dwindle rapidly in the last three years of the seventies; by 1885 the birds were scarce indeed. A resident of Red Bay whom I knew saw his last pigeon near there in 1893. As far as the whole Georgian Bay region is concerned the last word of the race’s obituary is this: in May of 1902 three pigeons - a pair and a single bird - were seen near Penetanguishene, Simcoe County.” (p.106)

Pigeons Over Fort Mississauga

There is another Ontario account that indicates just how plentiful the pigeons were in the late 19th century. It is easier to understand why there are no longer any passenger pigeons in the areas around metropolitan Toronto, however, since there is not much evidence now of any nature at all and few trees in which any kind of bird could roost. Around 1860 the area was not so barren. This description is from Ross R. King’s The Sportsman and Naturalist in Canada (1866):

Early in the morning I was apprised by my servant that an extraordinary flock of birds was passing over, such as he had never seen before. Hurrying out and ascending the grassy ramparts, I was perfectly amazed to behold the air filled, the sun obscured by millions of pigeons, not hovering about but darting onwards in a straight line with arrowy flight, in a vast mass a mile or more in breadth, and stretching before and behind as far as the eye could reach.

Swiftly and steadily the column passed over with a rushing sound, and for hours continued in undiminished myriads advancing over the American forests in the eastern horizon, as the myriads that had passed were lost in the western sky.

It was late in the afternoon before any decrease in the mass was perceptible, but they became gradually less dense as the day drew to a close… The duration of this flight being about fourteen hours, viz. From four a.m. to six p.m., the column (allowing a probable velocity of sixty miles an hour) could not have been less than three hundred miles in length, with an average breadth, as before stated of one mile.

During the following day and for several days afterwards, they still continued flying over in immense though greatly diminished numbers, broken up into flanks and keeping much lower, possibly being weaker and younger.

There are other accounts of large flocks, so many of them in fact, that at least some of them must have been witnessed by reasonable observers who had no need to dramatically exaggerate. This particular account by King has been subjected to some scrutiny which is provided here:

King never offered a numerical estimate, but Schorger, assigning two birds per square yard and a speed of sixty miles per hour, concludes that the flight involved an amazing 3,717,120,000 pigeons. At least three different scientists have each worked King’s data in recent years and come up with the same results as Schorger, although doubting that the pigeons would be flying at 60 mph as a normal speed during migration….Ken Brock of Indiana University Northwest created a graph showing the numbers of birds at speeds from 35 to 60 mph. But even at 35 mph, closer to the speed at which mourning doves fly, which is more unlikely given that the passenger pigeon was a far more accomplished flier than the dove , King witnessed over a billion birds passing over Fort Mississauga during the period of his observation.

Sources:

This is the place to begin: Project Passenger Pigeon. It is a tremendous website that is continually updated. There is a map one can click on to find information related to the area in which you reside. Canada is included and I learned that there are passenger pigeon skins, skeletons or mounts nearby at Western University and Medway High School.

This is the place to begin: Project Passenger Pigeon. It is a tremendous website that is continually updated. There is a map one can click on to find information related to the area in which you reside. Canada is included and I learned that there are passenger pigeon skins, skeletons or mounts nearby at Western University and Medway High School.

This book is as good as its title: A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction. Joel Greenberg. Anyone will find it interesting. I was going to get a copy for my grandkids to show them what has been lost, but the story is too sad and there are too many “carnivals of slaughter.”

The Sportsman and Naturalist in Canada is available in its entirety over the Internet. You will find the Fort Mississauga account at the beginning of Chapter VI, on p.121. See also A Feathered River… where several other descriptions are provided. The analysis of the report by King is found on p.6.

If you are really interested see Margaret Mitchell’s The Passenger Pigeon in Ontario. Although it was published in 1935, the University of Toronto Press has made it available over the Internet. Beginning on p.132 you will find a list of the “Last Reported Appearances in Ontario.” The last passenger pigeon reported in Middlesex County was in 1888 (p.135).